October 7th, 2022

The Life and Times of Garth Fergusson, Poet

Garth Fergusson, Poet

It has been my privilege to be friends with a poet from the time he was a teenager who worked as a high school intern for the Central Park Task Force, the small nonprofit organization that was the seed from which the Central Park Conservancy sprouted and grew to become a role-model public-private park partnership between civic New Yorkers and city government. Back in 1976, when the vision of a restored and well-managed Central Park was still a pipe dream, its chief workforce consisted of a few random volunteers and a group of summer interns assigned duties to help improve its horticultural welfare. One of them, Garth Fergusson, became a lifelong friend of mine as well as my daughter Lisa’s and son David’s.

You might call Garth a born poet, which is how I think of him. Recently he sent me his most recent series of poems, some of which which are thematically centered on the Covid pandemic. These are prefaced with the following brief biography that I asked him to write.

Garth Fergusson’s Biography

I was born in Jamaica in 1960 and came to the United States at the age of 12 to live with my father. My mother, who was chronically ill, thought that I would have better opportunities in America. In her words, she had done what she could for me and there was nothing more she could do that would change my life. Sending me to America therefore to live with my father was the best she could do for me. Immediately after I arrived in New York I realized that my father and stepmother’s marriage was toxic, and there was no room in the relationship for me. At first my stepmother directed her anger for my father at me, but as time passed and their relationship deteriorated further, she softened her tone; and my father, with whom I had no relationship at that point, predictably took that as a sign that I was siding with her and sought to get rid of me.

And in December of 1975, just before Christmas, Family Court granted him his wish and relieved him of his burden. The court made me a ward of the State of New York and placed me in St. Vincent’s Home for Boys in Brooklyn, where I would spend the next five years of my life. And after the hearing to decide my fate had ended, and since I had nothing with me except the clothes I was wearing and a few school books, I asked the judge if I could go back home to pick up a few belongings, and he said “No.” Home was no longer home. It was my father’s house and he did not want me there. My father was no longer my father. I was to have no further contact with him. He was no longer responsible for my welfare.

Early in the spring of the following year, since I would be sixteen by the time summer came around, I was given the option of going to summer camp in Pennsylvania with the rest of the boys or staying here in the city for the summer on the condition that I would have to work. I had no interest in going to summer camp; hence I had to find a job. I was not interested in the typical teenage summer job of make-believe work; I wanted something that was more meaningful. I thought of applying for a job in a national park, but the deadline for applying for a federal summer job had passed, and just at about that time, I received word that my mother had passed away in Jamaica, and I turned my attention to attending her funeral.

When I returned to school Mr. Orange, my botany teacher, asked me why I was absent from his class. I told him what had happened, and he said you are now on your own, alone in the world, and you will need to work to support yourself. It was from him that I learned of the Central Park Task Force (now the Central Park Conservancy). He said Bob Finkelstein was looking for high school students to intern in Central Park in summer, and it would be a good experience for me because I would gain valuable work experience. He asked me if I was interested and I said “Yes,” and he made arrangements for me to see Bob.

My performance during the interview was at best shaky. After all it was my first interview ever. I was raw and did not know what to expect. I answered his questions to the best of my ability. I was polite and did not do anything to offend him. From the other side of the room a female whom I thought was Bob’s secretary kept butting in to ask questions. I was perplexed as to why his secretary was asking me all those questions. It was a good thing I was polite to her too, because later that summer I would learn that she was Bob’s boss, not his secretary, and much later, after I had gotten to know her better and she had invited me to her house, and after she had asked me to babysit her son because she thought he needed a brother, I would learn that she was the one who decided to hire me, that Bob thought that I was a weak candidate and had had someone else in mind, but she wanted to give me a try. And since that fateful day in April of 1976, I have remained friends with Betsy and her family, and would work many more summers in Central Park.

As if preordained I discovered poetry at Walt Whitman Junior High School in Brooklyn, where I found that I had a knack for stringing words together to form images that expressed more than literal meaning, and I had a natural affinity, of course, for Whitman’s poetry, which was open and pulsating and free. And while the Shakespeare sonnets I read were great, and I enjoyed them, the form did not work for me. The sonnet was too restrictive and alien. It did not permit me to express myself in a manner that was natural. Free verse was the vehicle for me.

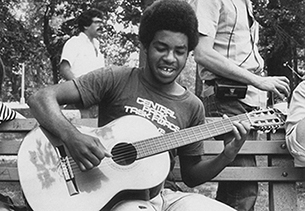

Poetry was not a part of life at home, but there was music, and since my stepmother was always asking me what I was going to do with my life since I would not be living with them forever, I decided that I would become a songwriter, but I knew nothing about music. Next step then was to learn to play an instrument.

That opportunity came in December of 1974 when my father decided that he was not going to give me a gift for Christmas. Finding his action unacceptable, even though their relationship had reached its end and they were no longer speaking to each other, my stepmother screamed at my father, and he relented and gave me twenty dollars to buy whatever I wanted. I remembered that I had seen a guitar in a pawn shop on Flatbush Avenue, and I went there and bought it.

It was not a good guitar, and I knew not what to do with it. I bought a How to Play Guitar book, but it did not help. So when it was time to apply to high school I applied to Edward R. Murrow, which had a music program. And it was at Murrow where I began to learn to play the guitar. I would skip lunch and spend all of my free time in a practice room with one of the school’s guitars. And the more I practiced, the more I dreamed of becoming a guitarist. Music then became the driving force in my life.

It was not a good guitar, and I knew not what to do with it. I bought a How to Play Guitar book, but it did not help. So when it was time to apply to high school I applied to Edward R. Murrow, which had a music program. And it was at Murrow where I began to learn to play the guitar. I would skip lunch and spend all of my free time in a practice room with one of the school’s guitars. And the more I practiced, the more I dreamed of becoming a guitarist. Music then became the driving force in my life.

After three and a half years I graduated from Murrow in the winter of 1979 and was accepted into the music program at Brooklyn College; I spent one semester there. I then spent two years at the State University of New York at Fredonia and two years at the Berklee College of Music in Boston before deciding that I did not have the ear for music; music was not going to be my life; I had to do something else; my ear was more suited for poetry.

Upon my return to New York in 1985, I began working full time as a temp in the mortgage-backed securities unit at Met Life. After one year I was hired full time to work in the medical claims unit. Unable to adopt to corporate culture, a year later I left for Beth Israel Medical Center. After two years and two different positions in their billing department, I became a research assistant at their Chemical Dependency Institute, and at around that time, I reenrolled at Brooklyn College and completed my BA in English in 1994, and in 1998, received a master’s degree in English from Lehman College.

In total, since my summers working in Central Park, I have held more than twenty different positions. Most recently I have worked as a special contract investigator for various federal agencies and worked on numerous public health studies funded by the state, city and federal government.

These poems are my personal account of the last two years of the pandemic. The form of each poem was determined by setting and situation. No overt attempt was made to craft a particular style.

The Virus Speaks: Poems of a Plague Year

By Garth Fergusson

Coronavirus Virus Quandry

Wednesday, April 8, 7PM, 2020.

Another ambulance

screams down the boulevard,

wailing and slashing the windowpane

with a rainbow

of flashing lights.

A few weeks back

I would not have peeped

through the blinds

for a glimpse

of whom it could be.

Now I do

to quench my curiosity.

Is it a friend

or someone I met recently

in passing?

I don’t know

but I wonder,

knowing

I may never see him

or her again.

_

Coronavirus Exodus

I am in Downtown Manhattan.

Delivery trucks, cabs, office employees, residents –

All appear to have fled in a hurry.

I look up at the buildings in the gray sky.

Evacuated and silent, they look like monuments

from a previous age waiting for

historians to tell their story.

_

Coronavirus Eternity

I have stopped waiting

for the pandemic to end.

Endings can be drawn out

and can be unpredictable.

One could wait for eternity

when there are other things

one could be doing.

Spring is here.

One year has passed.

It’s time to move on.

Soon weeds will sprout from the soil,

and wild daisies and dandelion

will bloom by the roadside,

pulling us out into the light of day

to forage for a cup of tea.

_

Coronavirus Politics

Feeling the heat from a steamy July, without consulting the virus,

politicians have announced that we are back to normal, and

we can go back to the lives we had before the pandemic began.

The question I would like to ask is: what is normal?

And why go back? Why not go forward—into that which we do not know?

_

Coronavirus Traveler

The virus is back. Where did it go? Nowhere!

It was here all along: sleeping under the bed,

roosting in the trees, riding the subway unseen,

reading magazines about its demise,

mingling with the crowd on a busy sidewalk,

and dancing with revelers in the park. No,

it didn’t go anywhere. It was here all along,

biding its time, waiting for the right moment

to manifest itself again, deep inside the gut

where it loves to breed.

_

Coronavirus Revenge

With the frenzy of flies

circling the carcass

of a wild animal, politicians rush

to be the first to issue mandates,

to say, “Do as I say or

I will step on your neck;

I will crush your windpipe,

or I will whip you into submission

with my cane

until you peel like an orange.

I am merciless, omnipotent;

I answer to no one.

You are just a tool for my ambitions

and I will not tolerate your disobedience.

Look at me. I am beautiful.

Adonis would be envious.

Every morning I look in the mirror

and smile with myself,

my beautiful physique, my perfect body

Share