December 11th, 2023

Designing the Central Park Luminaire: Nature as Ornament

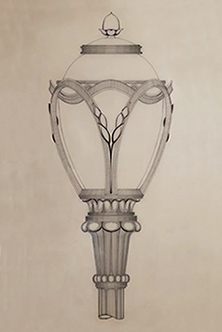

Bacon’s B Pole base.

Because the original design concept of Central Park as a rus-in-urbe – rural nature as an antidote to the metropolitan hardscape – influenced the design of Central Park, nighttime lighting was not included in Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s 1858 Greensward Plan. For reasons of visitor safety strolling in the park after sunset was forbidden until 1910 when, realizing that nighttime illumination would be a necessary safety feature as well as a nocturnal amenity, the Central Park Commissioners engaged the Beaux Arts architect Henry Bacon, architect of the Lincoln Memorial, to design what known as the “B,” pole with a lamp incased by a decorative shield of wrought-iron metal design. By the 1960s when the park was experiencing a mounting decline of its former beauty with a lapse in prior maintenance standards and the negligible, if any, enforcement of existing rules and regulations, its plight was accentuated visually with the vigorous smashing by vandals of many of its 1,600 lighting fixtures.

When the Central Park Conservancy’s design-and-construction office began its restoration planning of the park’s circulation system of pedestrian paths and vehicular drives, it was evident that the New York City Department of Transportation’s commercially acquired luminaires, which were then being powered by high-pressure sodium batteries were in the process of acquiring metal halide bulbs which emits an orange-tinted atmospheric shroud that made the park’s green vegetation assume a grayish tone visually. This crepuscular oddity made walking along the park’s paths after dark a nerve-wracking experience, which was only mitigated when LED bulbs became the agency’s fixtures of choice.

Light bulbs themselves are the electrical source that is emitted in rays through the sculptural glass vessels that loosely encase them, thereby creating the luminaire in total. In sum, the Central Park luminaire can be characterized as upside down glass urn cum lantern secured with metal ribs, giving an artistically conceived shape to the electrically powered bulb’s loose transparent casing.

It is hard to remember now how pervasive the cautionary words “Don’t go into Central Park at night,” once were. As long as newspapers carried stories of stalking muggers’ holdups of their human prey in secluded parts of the nocturnal park, this universally typical piece of advice implied that turning night back into day in Central Park every time the sun went down was the proper crime deterrent. Reinforcing this cautionary attitude, New York newspapers never failed to report the robberies, rapes, and the rare murder committed in the park. Thus, criminal assaults in the New York City Parks Department’s emerald crown jewel inevitably raised a flag of fear in many quarters.

A victim’s celebrity was naturally fodder for the press, as was evident in the report of the New York Times On November 29, 1979, the day after Andrew J. Stein, the Manhattan Borough President, was robbed of $100 by two youths with knives as he and his fiancée were walking his dog at the edge of Central Park.

The commissioner’s comments to the newspaper reporter resulted in the following article:

“We’re just a little shaken up,” said Mr. Stein, who was unhurt. At about 10:30 P.M., he and Brenda King were at the entrance to Central Park at 76th Street and Fifth Avenue when “all of a sudden these two kids stuck a big knife in my back and one in my fiancée’s back.”

“They said: ‘O.K. we’re going to cut you up bad,’” Mr. Stein recalled. “They stuck the knife to my throat, to my chest. I gave them my wallet and my address book. Thank God my wallet had $100 in it. That satisfied them.

“I’m really angry,” he said. “I realize now – I go to meetings, I hear people who were mugged at knife point. It was just stories. I’ve lived 34 years in New York City and nothing ever happened to me. And now the thought of punks like that getting off with a slap on the wrist or no incarceration. It was just a couple of inches, they could have slipped that knife into us.

The scion of as wealthy family, Stein must have had some kind of financial connection with the beer-brewing company Anheuser-Busch, since it was from this source that he was able to get a pledge for payment of the re-lamping of Central Park with a new array of light fixtures. The design cost for this project would be donated to the New York Department of Parks and, with Commissioner Gordon Davis’s blessing, the project would be part of the fulfillment of one of the Central Park Conservancy’s recently inaugurated restoration goals, which called for substitution of the mass-manufactured “gum-ball machine”-style fixtures that DOT routinely ordered after the ones in the style designed by the park’s original lighting architect Henry Bacon were too costly to be custom manufactured.

It was the late Gerald Allen (1933–2022), architect and Yale School of Architecture professor whom I had commissioned to be the designer of the restoration of the Cherry Hill horse-drinking Fountain and its surrounding circular brick terrace on the site that mid-twentieth century Department of Parks commissioner Robert Moses had supplanted with a parking lot. Allen was prompt to acquiesce to my request that that he envision an appropriately graceful replacement for the current off-the-shelf fixtures of DOT’s choice.

To undertake this assignment he immediately turned to Kent Bloomer, a fellow Yale School of Architecture professor, who at the time of the reign of modernism as the prevailing design style practiced by the profession’s most eminent firms and taught in prestigious architecture schools like Yale, was charting a new path that he would articulate in The Nature of Ornament: Rhythm and Metamorphosis in Architecture (Norton, 2000), an architectural students’ primer in which Bloomer follows in the footsteps of Owen Jones and John Ruskin, whose theories of architecture fostered the use of images relating to forms of vegetation and wildlife as integral embellishments in the Victorian architect’s design repertoire. This can be seen within Central Park in Jacob Wrey Mould’s design of the four-seasons-themed flanks of the dual staircases leading from the terrace beyond the north end of the Mall to the Bethesda Fountain.

To undertake this assignment he immediately turned to Kent Bloomer, a fellow Yale School of Architecture professor, who at the time of the reign of modernism as the prevailing design style practiced by the profession’s most eminent firms and taught in prestigious architecture schools like Yale, was charting a new path that he would articulate in The Nature of Ornament: Rhythm and Metamorphosis in Architecture (Norton, 2000), an architectural students’ primer in which Bloomer follows in the footsteps of Owen Jones and John Ruskin, whose theories of architecture fostered the use of images relating to forms of vegetation and wildlife as integral embellishments in the Victorian architect’s design repertoire. This can be seen within Central Park in Jacob Wrey Mould’s design of the four-seasons-themed flanks of the dual staircases leading from the terrace beyond the north end of the Mall to the Bethesda Fountain.

Bloomer’s Luminaire atop the Bacon’s B Pole.

As it happens, Bloomer was a friend of mine when he was an architecture student at MIT and I was an art history major at Wellesley. From my familiarity with his innovative graphic sensibility in the lively pen-and-ink cartoons he drew in his spare time as well as his general disregard for avant-garde modernism in architecture I was pleased to champion his design for a new Central Park luminaire. Linearly elegant, not satirical, in this case, the luminaire drawings echoed the naturalistic motifs of circumferential chains of seeds and leaves defining the segmented stages and flaring bases of Henry Bacon’s B Pole.

As opposed to the contemporary Bishops Crook Pole with its luminaire suspended from a downward curving arm at the top of the pole, the Bloomer design, like that of Bacon’s original design, which originally appeared in the lights erected on the Mall, upheld the luminaire from the top of the pole by a circular flange girdling it like the cupped sepals of a calyx embracing the stem of a flower in bloom.

_

Because Central Park was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1963, then placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966, and eight years later designated a New York City Scenic Landmark, all proposed alterations to its landscape and architectural features had to be approved by the New York City Art Commission, the New York City Landmarks Commission, and the New York State Department of General Services.

The luminaire design documents that the Central Park Conservancy presented to these agencies for review according to law received some heated discussion before receiving final approval.

An August 28, 1983, article in the New York Times summarizes the situation thus:

Designing the lamp fixtures being installed in Central Park raised questions about historic preservation for the designers of the lamps and the three city agencies that had to approve the designs.

The issue was whether to make the lights historical or contemporary, figurative or abstract, or a combination of styles, a debate surrounding much of the restoration of the park.

The designers, Gerald Allen, a New York architect, and Kent Bloomer, a professor of architecture at Yale, designed the fixtures over nine months, starting in the fall of 1980. They worked with the three agencies charged with passing on the designs, the Departments of Parks and Recreation and General Services and the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

One might call Bloomer’s luminaire, which is now sold nationwide, a graceful feat of naturalistic curvilinear industrial sculpture. Nevertheless, during the design approval process, the professional opinions of some of the commissioners of the three review agencies sometimes stymied the Conservancy designers advocating the Bloomer design. However, after several public hearings and design tweaks by Bloomer including the design of its acorn finial which had gone through two design reiterations and was no longer a matter of contention, the specifications for the luminaire’s mass production had reached their final documentary state and were ready to send to a lighting manufacturing company.

One might call Bloomer’s luminaire, which is now sold nationwide, a graceful feat of naturalistic curvilinear industrial sculpture. Nevertheless, during the design approval process, the professional opinions of some of the commissioners of the three review agencies sometimes stymied the Conservancy designers advocating the Bloomer design. However, after several public hearings and design tweaks by Bloomer including the design of its acorn finial which had gone through two design reiterations and was no longer a matter of contention, the specifications for the luminaire’s mass production had reached their final documentary state and were ready to send to a lighting manufacturing company.

The new Central Park luminaire soon became such an outdoor lighting design success that it became popular nationwide to such an extent that when I find myself gazing at one in a park or promenade in another city today I feel as if I am saying hello to an old friend.

Back home, depending on the weather, I enjoy walking in the park at any time of the day, but it is particularly pleasant to notice a couple of hours before sunset that an automatic timer has switched on the park’s luminaires. At such moments as this, I feel a flush of pride in myself for making this early park restoration project a signature design accomplishment of the Central Park Conservancy, which I gratefully attribute to my college friend Kent Bloomer whom I now mourn because of his death on October 23, 2023, one week before these words are being written in praise of how he made a great work of land art – Central Park – safer and more beautiful with a gracefully ornamental work of industrial art.

Share