February 3rd, 2024

Part Two: Central Park as An Outdoor Museum

Landscape design in which surface soil is fashioned into hills and dales and existing rock outcrops serve as the bones that determine its topographical physiognomy does not fall into the category known the fine arts, which is commonly defined by works painted on canvas, carved in stone, or modeled from clay to form a mold to be cast in metal. “Art within art” is therefore how I see the monuments, memorials, and bronze animals in Central Park.

To consider this to be the case, one must note that the idealism of the first half of the nineteenth century was replaced after the Civil War by a new, more direct naturalism. Although neoclassical sculptors continued to work in Italy, idealized subjects carved in marble gave way almost entirely to portraiture executed in bronze. Hesitantly at first and then with more assurance, sculptors learned to exploit the plasticity of this metal, to model it expressively, and to apply deep, rich patinas, and often gilding, to its surface.

In both the postwar North and South, there was a demand for public statues to honor the nation’s governmental and military leaders along with the soldiers who fought under their command. Pragmatic, self-made individuals, mid-nineteenth-century American artists did not have the intellectual ties with antiquity that their predecessors had had, and the subjects of their sculptural portraits were represented with direct, objective naturalism whereby they were depicted simply as men rather than gods in disguise. Although sculptors of the period continued to derive the poses of their subjects from classical sources, it was these artists’ realistic rendering of them in true-to-life poses that best characterized American sculpture of the post-Civil War period.

Indian Hunter by John Quincy Adams Ward

The vigorous realism of John Quincy Adams Ward’s Indian Hunter marked the end of neoclassicism and the beginning of an era in which naturalism dominated American sculpture. Ward’s maquette of Indian Hunter, which was displayed at the National Academy of Design in 1862, enlarged to its full size in 1866, and situated a few away from the west side of the Mall within the stand of elm trees across from the Sheep Meadow where it retains the distinction of being the first piece of American sculpture to be placed in the park as well as one of the most popular outdoor statues in New York City.

American pioneers had lived in proximity with wild beasts and, like their Native American co-inhabitants of the frontier, depended upon them for food and clothing, but in the years following the ‘Civil War, scientific curiosity and game hunting for sport fostered an interest in wild native beasts, exotic animals. Simple awe at their existence and fascination with their physical appearances is an eternal trait of humankind. This type of sculpture was born in France, where a group of artists referred to as animaliers devoted their energy almost exclusively depicting dogs in bronze.

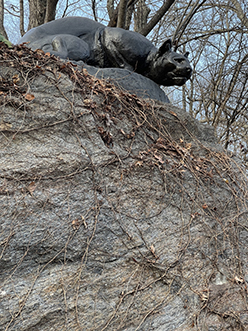

Still Hunt by Edward Kerneys

Two works by French animaliers were placed in the vicinity of the Mall in the 1860s: Christian Fratin’s Eagle and Prey in 1863 and August Cain’s Tigress and Cubs in 1867 (later relocated to the Central Park Zoo). These works undoubtedly influenced Edward Kerneys (1843–1907), America’s first animal sculptor, whose statue Still Hunt was dedicated in the Park in 1883. Kerneys had become obsessed with the desire to be a sculptor while working as an axman in the engineer corps laying out Central Park in the late 1860s. In 1876 he wrote that he was contemplating “modeling a life-size panther he named Still Hunt crouching from some rocks. However, it was not until 1881 that he was asked to enlarge the statue for Central Park. Situated on the ledge overlooking the East Drive at 76th Street, Still Hunt is not merely an anatomical study but a sensitive modeling of form that holds compressed all of the tension and power of the animal.

The French animaliers were part of the larger influence that French art exerted on American tastes during the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Often called the Gilded Age, this was a period of unparalleled growth and extravagance in the United States. Powerful businessmen, financiers, and their families increasingly controlled the wealth of the nation. They fostered a flamboyant material opulence, thereby assembling impressive collections of European art and encouraging American artists and craftsmen to work together to build and decorate their lavish mansions. These artists received most of their training and inspiration abroad, generally in Paris at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.

Eagles and Prey by Christophe Frantin

With regard to sculpture, Beaux Arts naturalism, which was not meant to control or dominate its setting but contribute to the total effect of the surrounding space, provided an ideal aesthetic for exalting the ferocious grace of certain animals as in the case of Eagles and Prey by Christophe Frantin (1801–1864), which is situated beneath the western grove of elms beside the Mall.

More contemporary than works by Beaux Arts animaliers is Group of Bears by Paul Manship (1886–1996). Cast in 1960 and unveiled on October 11, 1990, it depicts a mother bear and two cubs on a circular stepped pedestal in the center of the Pat Hoffman Friedman Playground next to the Fifth Avenue park entrance beside the 79th Street Transverse Road.

Group of Bears by Paul Manship

I have a special relationship with this sculpture since its presence in the park and popularity as a conspicuously fine work of animal art repurposed as an imaginative piece of playground equipment is due to a decision of mine during my time as Central Park administer and president of the Central Park Conservancy. Call it a surprise gift, because it is the result of a call I received out of the blue in 1988 from a gentleman named Samuel Friedman, who had spotted the Manship sculpture in the large sidewalk-display window of the Graham Gallery at 78th Street and Madison and on a whim decided to purchase and site it in Central Park in memory of his late wife Pat Hoffman in a location yet-to-be-determined. I was happy to propose the acceptance of the gift to the Conservancy board after meeting this friendly, dapperly dressed octogenarian who was wearing a summer seersucker suit and straw boater when we rendezvoused two blocks south of the Metropolitan Museum at the park’s east entrance gate next to the 79th Street Transverse, an open spot along the park perimeter’s interior, which had been designated by the Conservancy’s restoration planners as a site for a playground to replace the small rectangular one on the opposite side of the path that had been donated by the Lehman family during the Robert Moses era as parks commissioner. Sam was delighted with the proposed location and the suggestion that the Manship Group of Bears would become the kid-friendly centerpiece of a new well-designed playground. I asked landscape architect Bruce Kelly, one of the Conservancy’s four principal restoration planners, to design the new playground, and Sam was delighted with the choice of its location adjacent to The Met and the decision that the Manship Group of Bears become its kid-friendly centerpiece.

Today, Bruce’s playground design featuring an American masterpiece of animalier art has been a great success for more than thirty years, proving that, as much as with play equipment specifically designed for the exercise of young bodies, Manship’s Group of Bears invites climbing and sliding about the sculpture’s smooth surface and, by the energetic buffing offered by the seat and legs of their pants, giving the bronze patina a golden sheen.

Central Park’s most prolific animalier, Frederick George Richard Roth (1872–1944) was a well known as a sculptor of living animals including Dancing Goat, designed as decoration to the northern entrance of the Central Park Zoo. It portrays this fanciful creature in a playful and humorous manner, accentuating its capricious character by the contortion of the goat’s body from lifted thighs to twisted head, which is enhanced by a sense of kinetic energy and rhythmic movement produced by the positioning of its hoofs, and the richly modeled variegated surface texture. Dancing Bear, also by Roth, is a companion sculpture to Dancing Goat symmetrically positioned in a second narrow alcove in the Zoo’s northern entry wall.

Balto by Frederick George Richard Roth

Roth’s freestanding masterpiece is identified by a plaque bearing the words ENDURANCE FIDELITY INTELLIGENCE, which is affixed to a glacially deposited boulder atop a Manhattan schist outcrop. Its subject is a black Siberian Husky named Balto, which became a canine celebrity as the representation of an indomitable leader of the team of seven sled dogs that relayed antitoxin six hundred miles over rough ice and treacherous waters from Nenana to the relief of stricken Nome in the Winter of 1925, thereby saving the residents of that city from a diphtheria epidemic.

Park visitors walking alongside Balto on the path leading to the arch that carries the visitor beneath the East Drive to the Mall inevitably notice the perennial sheen of buffed bronze due to the fact that almost every child who encounters this sculpture immediately climbs upon the dog’s back and slithers along its surface, with feet dangling atop its flanks and paws.

Roth’s fifth statue in Central Park, Mother Goose, was erected in 1938 in the playground named in honor of Mary Harriman Rumsey (1881–1934), a well-known philanthropist and social reformer. With popular children’s literature a now accepted genre for statuary in the park, George Lober’s statue of the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen (1956) and José de Creeft’s Alice in Wonderland (1960) were installed in proximity to the Model Boat Basin, the setting for E. B. White’s classic children’s book Stuart Little. De Creeft’s sculpture, which is placed upon on a granite stage designed by Hideo Sasaski, has taken on a beautifully polished patina as a result of the thousands of children who have climbed over and nestled in crevices of the eleven-foot-high statue. The work, a congregation of figures and vegetation, portrays Alice seated on a large mushroom with her kitten Dinah crawling on her lap and surrounded by other characters from Lewis Carroll’s whimsical classic, including the March Hare, the Dormouse, and a small crocodile.

Alice in Wonderland by José de Creeft

De Creeft was one of the earliest and most talented of the school of sculptors referred to as direct carvers. In his seventies when Alice in Wonderland was modeled, his ingenious handling of the statue’s masses and voids and the imaginative arrangement and representation of its figures resulted in the humorous aspect of this large bronze composition, which has been enhanced by the continuous contact with children’s clothing it continues to receive.

Share