October 16th, 2022

Hill Country Journal

Although I have been adopted New Yorker by happy circumstance and desire for the last sixty years, the word “home” has special resonance for me. Today it is associated with my high-floor upper West Side apartment one-half block from the 81st Street entrance to Central Park. Still, I cannot forget my Texas origins and my first home, which was custom-built in the Monterey Colonial style by my parents in the Alamo Heights neighborhood of San Antonio. (Monterey Colonial residential architecture is characterized by being two stories high with porches on both the first and the second floors. North of the Border its wooden siding gives it more of an American suburban cast.)

The Browning siblings in front of their childhood home on November 7, 2022.

On my occasional trips from New York City to Texas I usually drive by 414 Castano with my brothers Robert and Jamie to have a look-see at what was their first home too (the current owners don’t seem to mind this brief trespass).

Digging deeper into my heart, I find my real first home on the 979-acre ranch my father bought for his growing family in 1942 as a weekend and summer retreat. Located sixty miles north of San Antonio “deep in the heart of Texas,” a cause for a kind of localized chauvinism in my youth, this is the place of my nature-loving childhood is the one that evokes my sentiment of the meaning of “home.”

Join me if you wish to take the trip I made just a few days ago from San Antonio to the ranch. Here are the directions: Driving north from San Antonio, upon reaching Johnson City you take a right turn off of Highway 281 onto County Road 2766. In four miles you will be at the entrance to the Browning Ranch. Open a gate with the initials CL (my father’s first name) emblazoned on plaque fastened to its metal bars. Passing across the cattle guard, you continue on what now has the postal address of 159 Browning Lane. In a few yards as you look off to the left you can see in the middle of the field behind a barbed wire-fenced a more-than-a- century-old live oak “tree,” a second word in my trio of sentiment-provoking words and one that, depending on location, is often affiliated with “home.” Whenever I approach this landmark I feel like a character in the succession of protagonists in the short story-like chapters of Richard Powers’s The Overstory, each of whom has a youthful passion for a particular tree. But now, writing these words, I feel as if I am composing an obituary, for I am saddened to say that two years ago the tree with its wide canopy of sunlight-reflecting live-oak leaves and gnarled rough-bark branches, which becomes more precious to me as my age approaches its own, had been struck by lightning and was now but a skeletal presence. To cut or not to cut for firewood: this was the question that I answered in the negative. Skeletons of revered remains have been universally preserved through the ages, so why not let this relic be one for me, I reasoned.

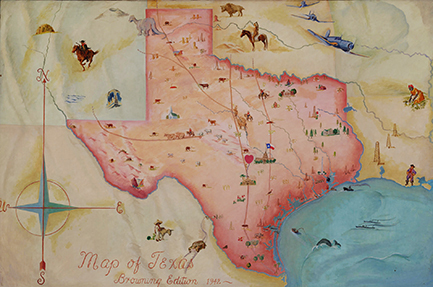

Turning now to the word “love,” I will say that, next to Central Park, the ranch is the dearest place I know, and being at the ranch in person always brings to me a pleasant jolt into the past. Feeling the presence of my parents still there (I have never altered the ranch house or its furnishings in any way), I often like to put my current observations and reminiscences on paper as I sit next to the big fireplace with the oil painting of a map titled “Deep in the Heart of Texas” over the mantel piece. Such is the case as I write these words now and so it was on a visit almost twenty years ago when I wrote an essay I titled Hill Country Journal, which I recently discovered during my current binge of home-storage reorganization.

To come to the third word I have signified as emotionally resonant, on my recent trip to the ranch my emotional sensation of the word “love” was not only one of place but also of family. This is so because this most recent trip to the ranch included the presence of my children Lisa Barlow and David Barlow together with our Sunday visitor, my niece Helen Browning Silantian.

To come to the third word I have signified as emotionally resonant, on my recent trip to the ranch my emotional sensation of the word “love” was not only one of place but also of family. This is so because this most recent trip to the ranch included the presence of my children Lisa Barlow and David Barlow together with our Sunday visitor, my niece Helen Browning Silantian.

Now that we were all sitting together in the living room after lunch, they were obliged to walk with me down one of my favorite stretches of memory lane as I continued to give all within earshot conversational snippets of my childhood recollections. Lisa, David, and Helen, along with Helen’s husband John Silantian and my Ted, were thus captive listeners to the words, “I remember when” followed by an anecdote that often included, beside my young self, my brothers Robert and Jamie and our parents Elizabeth (Betty) and Caleb Leonidas (CL) Browning. With the exception of Ted, Alan, and John, whose happy boyhoods were respectively spent in Ohio, New York State, and Rhode Island, and my father and mother who, being deceased, could not be with us, these recollections of mine chimed with their own memories of this place.

Later, after our guests were gone and day had turned to night, Ted called me to come outside and watch the blood moon rising over the ranch’s west ridge. David joined us and pointed out the planet Jupiter shining not far away from the moon in the night sky. Close to the ground another light shone, which was the flashlight signaling that Lisa and Alan were taking a walk along the path that leads to the creek. After this beautiful close to a beautiful day, I sat down on the sofa in front of the fireplace and re-read my recently discovered May 12, 2003 Hill Country Journal.

The season of the year did not permit me to gaze into a burning fire made of live oak logs as had been the case when I wrote it, but the “Deep in the Heart of Texas” oil painting and the book cases on either side of the mantel that still contain the books my parents had placed on their shelves over a half-century ago gave me a warm sense of my good fortune in being able to experience a continuity of the present with the past. I would soon be lying in the same bed mentioned my twenty-years prior journal’s first sentence.

_

Hill Country Journal: Monday, May 12, 2003

I awake in the corner of the dormitory-style sleeping-porch of my childhood in the ranch house built by my parents in 1942 four miles east of Johnson City, Texas. The urge to doze for another hour fanned by the sweet pasture-smelling breeze of the spring morning fights with the urge to remember and write. Writing – that fragile bulwark against multiplying senior moments and the morphic blanket of time that deposits its minutes and hours and day in accreting strata of an anecdotal record, the skeletal biography of fossilized experience that historians, both academic and popular, may turn into factual or fictional narrative, a malleable material that will be mined and reworded by future writers of revised narratives of time and place.

The boldest literary rescue operation, the great synthesis of word and remembered experience is in the left-hand bookcase of the two that frame the fireplace built of native limestone. I run my fingers over the long dark wood mantle that stretches between them above the fireplace. It is now spring but the fireplace still contains the ashes from smoldering coals and charred remains of the live oak logs chopped from the trees on the ranch to build it.

Above the mantle is the painting commissioned by my mother at the time the house was built, a large map of the state of Texas depicting anecdotal vignettes based on regional lore and family history. Before I start to gaze at it as usual, identifying each of its symbols as I run my eyes across it, I reach up and pluck from the third shelf of the left-hand bookcase from where it has reposed for more than sixty years my parents’ 1934 Modern Library edition of Proust’s masterpiece and started to read from the first of its now-yellowed pages, “I would ask myself what o’clock it could be; I could hear the whistling of trains, which, now nearing and now farther of, punctuating the distance like the note of a bird in a forest, showed me in perspective the deserted countryside through which a traveller would be hurrying towards the nearest station—the path that he followed to be fixed forever in his memory by the general excitement of being in a strange place, to doing unusual things, to the last words of conversation, to farewells exchanged beneath an unfamiliar lamp which echoed still in his ears amid the silence of the night and to the delightful prospect of being once again at home in its accustomed place.”

Above the mantle is the painting commissioned by my mother at the time the house was built, a large map of the state of Texas depicting anecdotal vignettes based on regional lore and family history. Before I start to gaze at it as usual, identifying each of its symbols as I run my eyes across it, I reach up and pluck from the third shelf of the left-hand bookcase from where it has reposed for more than sixty years my parents’ 1934 Modern Library edition of Proust’s masterpiece and started to read from the first of its now-yellowed pages, “I would ask myself what o’clock it could be; I could hear the whistling of trains, which, now nearing and now farther of, punctuating the distance like the note of a bird in a forest, showed me in perspective the deserted countryside through which a traveller would be hurrying towards the nearest station—the path that he followed to be fixed forever in his memory by the general excitement of being in a strange place, to doing unusual things, to the last words of conversation, to farewells exchanged beneath an unfamiliar lamp which echoed still in his ears amid the silence of the night and to the delightful prospect of being once again at home in its accustomed place.”

Putting Proust back temporary gap on the shelf where it belonged, I noticed on the mantle just below the lowest shelf two boxes of jig-saw puzzles cut from a wooden template hallmark of the earlier generations of these hand-crafted games requiring optical ingenuity and aesthetic concentration. I pulled down the 205-piece one with the manufacturer’s mark of Parker Brothers and the title “French Winter Scene,” a copy of a painting by Maurice Utrillo.

My sentimental survey of the ranch house and all of its familiar contents thus turned me in happiness to my own remembrance of things past from the time I was six-years-old until I left for college in 1953. I loved the house, and still do, because it is inhabited by memories of parents who built it as family weekend and summer retreat after my father had become a successful general contractor in San Antonio during the Second World War years.

Now the original 979-acres of ranch that was later enlarged by my father’s subsequent purchase of two contiguous Hill Country ranches had been owned by me since with my mother’s death in 1992. As her heirs, my brothers Robert and Jamie and I had an undivided interest in the entire ranch, which they wished to put up for sale. With my one-third share of the proceeds from the sale of the two subsequent ranch properties my father had bought, I bought them out of their share in the original home property. This was probably a dubious decision since my adopted lifetime home is New York City and I was therefore a long-distance owner and there were limited opportunities for my husband Ted and me to visit the ranch. I therefor turned the ranch house into a Bed & Breakfast operation, with the same old-time ranch manager continuing to live on the property and look after the place in a reliable but somewhat desultory way.

Now it was time for the B&B guests to work the two remaining jigsaw puzzles and sleep in the beds that were still so familiar to me. It was surprising then that this morning when I opened the box containing Utrillo’s winter scene, I saw on the back side of the lid the name of the Dowell family and the date April 19 of this year, which was just two weeks ago. I also saw beneath the Dowell’s inscription that my brother Robert had worked the Utrillo puzzle on December 24, 1992, the first Christmas after our mother’s death.

Picking up the second puzzle, titled “Two Points of View,” which had been made by the U-Nit Puzzle company located at 47 Beverly Road, West Caldwell, New Jersey, I noted that it had been worked by the Dowell family on the previous day. Whichever Dowell made this signature had appended a note saying that there was one missing piece in the shape of a pipe.

I too have worked these same puzzles here in this house and other similar well-crafted wood-backed ones over the years. I can actually remember completing “Two Points of View,” all except for the empty space in the shape of an old-fashioned, curve-stemmed pipe.

Sitting back down on the sofa facing the fireplace, I looked up at the ranch house icon, the painting commissioned by my mother and titled by an artist’s brush in a large flowing script “ Map of Texas – Browning Edition, 1942.” My eye began to rove over its topographically scattered vignettes. These include the Alamo; my grandfather the Rev. C. L. Browning’s first Methodist pastorate in West Texas; Southern Methodist University in Dallas where my father matriculated and pledged the Signa Alpha Epsilon fraternity; the Chisholm Trail of legendary cattle drives by cowboys; the Carlsbad Cavern (outside the map’s pink background in the beige vagueness of New Mexico; Bill the Kid on horseback and a crudely defined dinosaur lumbering out of the Texas Panhandle; a grazing bison and a Comanche warrior on horseback occupying the bluff on a topographically undefined territorial space on the map where Oklahoma would be; and three propeller airplanes flying into what signifies Louisiana where a Black woman wearing a bandana picks cotton; and a pirate swaggers beside the Gulf Coast. To the south a road winds into Mexico with a small sedan driving alongside a sombrero-and-serape-clad Mexicano and his burro, the two smudges inside the car presuming being my parents en route to Monterrey on a vacation.

The part of the map that fixed my attention as a child and now again is the deep pink heart with it interlocking letters C and L, these initials which he had adopted for a first name and then as a cattle brand (although not a rancher, my father ran a small herd of cows, a few for milking and others for sale as beef). Intentionally the proprietary rose-red heart was almost in the dead center of the pink background of the painting of the State of Texas. (How proud I was to believe that our ranch was Deep in the Heart of Texas, an observation that was borne out by the map artist’s inscription of these words on the decorative panel above the keyboard of white-painted piano on the north side of the living room.)

A few inches to the right (48 miles due east) of the cattle-brand initials signifying the position of the ranch in the Hill Country heart of central Texas is the representation of the state’s official political heart in Austin with Lone-Star flags hoisted over the dome of the capitol.

Austin is also the location of the University, and although not a prominent feature on the map, its proximity to me today is important since this trip to the ranch, which I have been eulogizing in this early-morning diary entry is not the principle purpose for my sentimental solo visit to the ranch at this time. It is also being undertaken with me wearing my professional hat as a landscape historian and park preservationist. This project is going forward because the Historic Preservation Department within the School of Architecture has recently, at my suggestion to Dean Fritz Steiner, has undertaken a semester-long student program to study the ranch as a historic Texas Hill Country landscape from geological, topographical, archaeological, and environmental perspectives. The Browning Ranch Cultural Landscape Report will be the result of the work overseen by Jeffrey Chusid and a graduate-student associate named Lara, who are supervising the project, and today I am here for a presentation of the students’ reports on their findings to date.

The time of the students’ term-end presentations has conveniently coincided with the my Saint Mary’s Hall class-of-1853 reunion in San Antonio. Now, after renewing old friendships with other grandmothers who have formed, at least for the precious moment, a joyous girlish camaraderie, I am back at the ranch I am back at the ranch digesting the information produced by Jeff’s students, taking long walks by myself, and bouncing in the white pick-up around the rough ranch roads with Scott Gardner, our twenty-seven-year-old new ranch manager.

Scott has been working in close association with Jeff and his students, and equipped with geographic information systems software he is supplementing their computer-generated data mapping with additional observations of the ranch’s environmental conditions and underlying physical structure as part of the Texas Hill Country.

Scott’s fiancé Colleen Lyons is an environmental educator on the nearby Selah Ranch, J. David and Margaret Bamberger’s 5000-acre role-model property for responsible land stewardship and best practices in Texas Hill country conservation. Colleen came over on Thursday to join the circle around the pine table in the dining area at the opposite end of the wrap-around porch that once served as a bunkhouse for the men who had been invited to my father’s deer-hunting parties, which is now used by our B&B guests, and where I have made my night-time next in my childhood dormitory.

Jeff had placed the Powerpoint projector and computer for the presentations that the students have prepared.

After the prehistory occupation of this part of Texas by Native Americans and the first white settlers’ hazardous relations with the Comanche, Lara gives her report on the geology and soils of the Browning Ranch.

A 1982 USCS topographic map is placed on the table along with several rock samples that the students have collected. These specimens physically encapsulate several eons of geologic activity during which time that the landmass of what is now the Texas Hill Country was part of the bed of the inland sea submerging much of central part of North America. It was their oceanic waters forming the cretaceous and earlier deposits that hardened into various strata of limestone that were later uplifted by geological forces to create the karstic Texas plateau that has eroded by dissolution to become ridges and valleys from which springs seep and streams flow – that is when there is sufficient rainfall.

When I came to the ranch this time I had never seen the place so gushing, sparkling rivulets coursing through the draws, splashing as miniature waterfall and tiny hidden grottoes revealed where after two month of drought had left only dry rocky beds gradually flowing down the hillsides to the ranch’s riparian corridor, Honeycut Creek.

Laura’s geology report relates to the rock samples on the table accompanying a geological map portraying a section of the creek and its surrounding slopes over several million years of geologic time, the most recent being represented by the Glen Rose limestone member, alternating beds of limestone, dolomite, marl, and clay, which form the ranch’s highest plateaus. Erosion has stripped away this material revealing on the lower slopes the Hensell member formed of predominately sand, salt, and clay and the Cow Creek limestone, originally a Coquinite produced by a multitude of the dissolved shells that form a highly porous, massive, light-colored, cliff-forming material that grades down to the Hammett shale, which is visible on nearby Miller Creek, but not on the ranch. Here there the Cow Creek limestone gives way where Honeycut Creek drops in its passage toward the Pedernales River to dark gray Marble Falls limestone and a small strip of micro-granular limestone and dolomite called the Stribling Formation.

The Marble Falls limestone is a rock of the Pennsylvanian period, while the Stribling Formation dates back to the Devonian. Where the Pedernales River makes a big arc known as the Honeycut Bend on the north side of County Road 2766 in the 100-acre section of the ranch called the River Trap Honeycut Creek has cut down into late Ordovician time to reveal the eponymous Honeycut Formation of cherty limestone and dolomite, which has its richest known sequence in the Honeycut Bend of the Pedernales.

A Hill Country geology lesson would not be complete without a discussion of the Edwards aquifer, as the water supply of Austin, San Antonio, and other communities in south central Texas, including our own ranch hometown of Johnson City, As the students’ presentation continued, I was able to realize the importance of the Karst formation – underlying limestone, which eroded by dissolution, producing ridges, towers, fissures, and sinkholes, which takes the form of a giant sponge composed of hard, calcium bicarbonate with interlaced chains composed of absorbent pores.

Ted had gone earlier with Scott to inspect the mountainous pile of cut cedar, which has revealed a six-acre landscape of grass and wildflowers studded here and there with the now liberated solidly compacted live oak groves compacted tree groves mottes. Here and there are scatterings of agarita (Mahonia trifoliolata), a native Texas shrub with holly-like foliage and red berries, along with some small persimmon trees here and there. This inspection tour with Scott was to show Ted an almost finished first attempt to control the invasive omnipresent cedar that has made a conquest of so much of the Hill Country rangeland, greedily sucking up water from the aquifer that has been furnished by creeks like Honeycut and other riverine tributaries. In addition, much of the rainfall that is captured by the brushy thick canopies of cedar quickly evaporates and is therefore prevented from dripping to the ground and recharging the water table beneath, which stymies its further absorption of by the underlying aquifer, which takes the form of a giant limestone sponge composed of hard, calcium bicarbonate with interlaced chains of absorbent pores.

It was eight o’clock, five hours, after the students began their presentations when one of them, a photographer, showed us the beautifully composed pictures she has taken of the ranch house, including details of hardware and wall surfaces, and the painting of the “Browning Edition of the Map of Texas with its bookcases on each end of the thick dark-wood mantel over the fireplace.

Scott and Jeff and I stand by the big suspended iron dinner bell saying our good byes in a pool of light from the annex to the carport with its screened enclosure for gutting and butchering the deer shot by ranch hunting parties and two Spartan rooms built for the “help” that came over the years, first to cook and clean for the growing family, then to cater the house parties for my father’s deer-hunting guests. A slab of smooth concrete nearby bears the worn red-painted markings of our shuffleboard court, a much-enjoyed recreational feature over the years, along with the twin iron rods that served a goal posts for games of horse-shoes and the back porch ping pong table.

I look up into the illuminated sinuous branches of the live oak trees that form a shady grove shielding the house from the daytime Texas sun, enjoying the cooling Gulf breeze. Rocking back and forth on the white-painted “settee” swing suspended from a wooden superstructure. I inhale the fragrant smell of grass dried cow dung and listen to the steady whine of cicadas. A bank of swallows’ nests of daubed material cemented to the side of the chimney where its limestone masonry meets the ceiling of the covered open-sided porch. This reminds me of the many mud nests constructed by the insects called daddy-long-legs that have been seen in the eaves and under the roof of this porch.

On my memory list I also check off the resonant sound of the kitchen door slamming behind me that registers in the barely conscious part of my brain the familiar confirmation, “Home again!” I go inside the kitchen too make a salad, braise a fillet of beef, and remove my baked potato from the oven. Soon I will be asleep in my mother’s heirloom double bed with carved posters in the central room she claimed as her own, while my father slept alone in the back bedroom unless there were overnight guests.

When I returned from my class reunion in San Antonio on Saturday evening Ted was there to greet me. He had spent the day with Scott and Colleen discussing the bee-keeping project that she has located in the vicinity of the creek south of the pasture where Scott has done an impressive amount of removal of the invasive undergrowth of Ashe juniper (cedar as it is called in these parts). This has been accomplished with a rented Bobcat utility vehicle, a chainsaw, and a set of hand-held loppers.

_

Ted had gone earlier with Scott to inspect the mountainous pile of cut cedar, which has revealed a six-acre landscape of grass and wildflowers studded here and there with the now liberated solidly compacted live oak groves compacted tree mottes (compressed groves). Here and there are scatterings of agarita (Mahonia trifoliolata), a native Texas shrub with holly-like foliage and red berries, along with some small persimmon trees here and there. This inspection tour with Scott was to show Ted an almost finished first attempt to control the invasive omnipresent cedar that has made a conquest of so much of the Hill Country rangeland, greedily sucking up water from the aquifer that has been furnished by creeks like Honeycut and other riverine tributaries.

In addition, much of the rainfall that is captured by the brushy thick canopies of cedar quickly evaporates and is therefore prevented from dripping to the ground and recharging the water table. This stymies its further absorption of by the underlying aquifer, which takes the form of a giant limestone sponge composed of hard, calcium bicarbonate with interlaced chains of absorbent pores.

_

During the time I kept this Texas Hill Country journal that I am now copying here I could not help having had in mind the field research underlying the rebuilding of the Central Park according to the principles Central Park Conservancy’s restoration and management plan of 1985, which I supervised as founding president of the Central Park Conservancy. Today I like to think of the ranch as a similar challenge in scenic and environmental reconstitution. For starters, there is the near parity of the two landscapes in terms of size – Central Park is 830 acres as compared with the ranch’s 979 acres. However, their respective landscapes are entirely dissimilar. The fact that one is a designed naturalistic landscape to provide scenic and recreational relief in a great city and the other is private property to enjoy as a rural retreat does not mean that there is a large distinction between them as landscapes to be stewarded in an environmentally enlightened fashion. In terms of setting out a multi-year plan for such a program, it is, as we are learning from Scott and the students’ Cultural Landscape Report, the natural history of a particular landscape is the key starting point. This is providing a needed education for me in understanding the fundaments of the place that, next to Central Park, I have most cherished in a deeply personal way during my lifetime.

Here we must start with Hill Country geology and the Edwards aquifer as the water supply of Austin, San Antonio, and other communities in south central Texas, including the ranch’s nearby town of Johnson City, I was able to realize the importance of this Karst formation as an imperative for land conservation. But there was much more to the ranch’s remarkable scenic endowment with ridge-upon-ridge separating numerous drainage basins beneath the big clear blue Texas sky and wildlife bounty of unique flora and fauna to inspire me to suggest to Ted that we could, following David Bamberger, a remarkable nature-loving landowner whose nearby 5,000-acre Selah ranch is a role model for enlightened environmental stewardship. It was Bamberger who introduced us to Scott and confirmed us in our new mission to make the Browning Ranch a conservation-worthy example for other ranchers as well as a restored part-time family retreat deep in the heart of Texas. Since Scott has a background in environmental science, it was logical that we should find institutional partners for ad hoc research projects that reveal the complexity of the ranch as wildlife habitat and help us demonstrate the benefits of intelligent water conservation, especially in an era of climate change, and sound practices for good land management as a time when much beautiful ranchland like ours is being divided into “ranchettes” for an increasingly large real estate market.

Ted’s tour of the ranch with Scott today has given us an appreciation of the ways in which he has proved that we were fortunate to find the right man for the job. As it happens, not only have David Bamberger done us a favor by introducing us to Scott, but we have done him a favor too since Colleen Lyons, the woman who is an indispensable aide to David’s wife Margaret as an environmental educator and organizer of visits by school groups to the Bamberger Ranch, will be married on October 25. This means that she will come and live on the ranch in the foreman’s home, which means that she will be only a short drive away from her daily job and therefore committed to stay in the area rather than find employment elsewhere.

But there is a problem with this arrangement at present because of the condition of the century-old house that has been the home of Anton Naumann, my father’s ranch foreman and until recently, Bill Watson, his son-in-law who worked for us prior to the hiring of Scott. The “Rock House,” as the students have designated it in their Cultural Landscape Report is in a condition of such dire dilapidation that we must consider building a new foreman’s house where Scott and Colleen can live. Ted and I have begun to discuss where on the property it might be located.

Scott has mastered a plan to systematically attack the problem of the vast amount of cedar overgrowth with our first piece of machinery, a Bobcat that he can operate with the help of one man, provide a cost-effective solution that is more respectful of the remaining vegetation and wildlife habitat than would be a clearing by contract operation, if Ted and I are able and willing to purchase a Bobcat for Scott’s fulltime use on the ranch. We do not yet have a firm idea of how long it will take under this management program for Scott to remove cedar from approximately 500 badly overgrown acres that still need considerable clearance, but the general neglect of the ranch’s management since my father’s death in 1970 has created a density of cedar that is startling in aerial photographs that show our property alongside that of a cedar-clearing neighbor.

Ted unfortunately could not join me for the students’ Cultural Landscape presentations, and yesterday – Sunday – he had to leave to catch a plane back to New York. I therefore have one additional day to think alone about the future of this land and take a walk to the creek in the evening. There will be estate-planning as well as land-planning issues to sort out in the future, but for now it is Scott and Colleen’s future that claims consideration.

Share