May 10th, 2025

The Saviors of Central Park: Part Six: Architectural Renewal

The overall restoration of Central Park is that of a naturalistic landscape with features for both passive and active recreation. The former are the province of landscape architects whose mandate is to provide visitor comfort and visual pleasure through the facilitation of contact with mowed grass, pruned trees, handsomely weathered rock outcrops, and scenic water bodies. The latter, on the other hand, pose physical challenges that require various forms of design and construction, thereby necessitating the services of an architect.

Successful park design, of course, necessitates a team approach in which architect and landscape architect work integrally. In my prior journal posting I introduced the reader to the four landscape architects – Marianne Cramer, Judith Heintz, Bruce Kelly, and Philip Winslow – whose collaborative talents – were seminal in the preparation of Central Park’s 1985 management and restoration plan. In this posting, I am introducing architect Jean Parker Phifer, who became a fifth, and invaluable, member of the team. Her personal account of the projects in which she was engaged during the more than 15 years during which she was commissioned to work of one project after another paints a vivid picture of the historical architectural expertise as well as her ability to collaborate with landscape-architect colleagues on various projects’ design specifications.

Evoking the Architecture of Historic Central Park through Restoration Design Projects by Jean Parker Phifer, FAIA

This photo, taken c.1980, includes from left to right: William Rogan, the architect for the restoration of the Dairy; James Marston Fitch, dean of the historic preservation program at Columbia University; Jean Parker and Philip Winslow who collaborated on the restoration of Bethesda Terrace.

My love of historic preservation reaches back to my undergraduate days at Yale, where I wrote my thesis on the original text with hand-drawn sketches for John Ruskin’s influential book The Stones of Venice preserved in the Beinecke Library, earning a prize in the art history department in 1974. When I applied to architecture school, I settled on Columbia because I could get a Master of Architecture degree while taking my electives in the pioneering Historic Preservation program founded by James Marston Fitch.

After two years working for the National Park Service to document and restore historic buildings as varied as 18th century Hampton Mansion outside of Baltimore, 19th century home of Martin van Buren in Kinderhook, NY, and 20th century Leeks Lodge, a log cabin in Grand Teton National Park, I decided to move back to New York City in 1979 to take a job with The Ehrenkrantz Group. My first, hair-raising assignment was to map the vertical cracks near the brick corners of the Chrysler Building from a narrow hanging scaffold that moved up and down the exterior façade!

In 1980, landscape architect Bruce Kelly recommended Building Conservation Technology, a subsidiary of The Ehrenkrantz Group, to consult on the restoration of structures in Central Park. I was assigned to meet with Betsy Rogers, and I remember her eye-opening tour of the park, emphasizing the experiential sequence that Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux intended for visitors to follow from Grand Army Plaza to the Belvedere Castle. But it was also clear that the park, with formerly grassy areas reduced to hardpan, historic structures defaced with graffiti, and an ominous sense of abandonment, was in urgent need of attention.

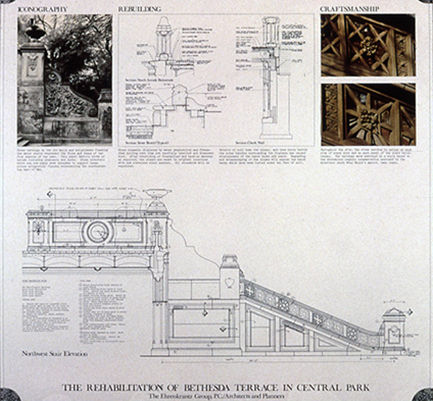

This presentation board shows the naturalistic iconography of the stonework as well as the sectional details for rebuilding and waterproofing the balustrades and benches.

Betsy asked me to undertake the restoration of Bethesda Terrace, designed by Jacob Wrey Mould, at the heart of Central Park. The terrace’s sumptuous carved New Brunswick sandstone ornamentation, which features carvings of flora and fauna of the four seasons of the year, was inspired by 19th century British theorists John Ruskin and Owen Jones. Similarly, the highly decorative encaustic ceramic tile ceiling of the underground Arcade linking the terminus of the Mall at the 72nd Street Drive with the circular apron of brick paving stones of the lower half of the terrace encircling the base of the Bethesda Fountain was composed of tiles produced by the Minton Company in Stoke-on-Trent, Great Britain’s leading ceramic factory well into the twentieth century. (The encaustic process, which achieves decorative patterning through the use of colored clays, not painted finishes, can be admired on the floors of the United States Congress in Washington, D. C., however, the ceiling of the Bethesda Terrace Arcade is the only known example in the world of encaustic tiles applied overhead. Their colorful design enlivens the below-grade Arcade, which links the terrace to the Mall via a wide stone staircase. It was clear at the time that the restoration of the Bethesda Terrace and Arcade was compromised by the fact that the Arcade’s ceiling tiles needed comprehensive conservation and the steel plates supporting them needed to be replaced. This added a difficult new dimension to the architectural requirements of the restoration plan for Bethesda Terrace from its upper balcony next to the 72nd Street Drive to the curbed shoreline of the rowboat Lake.

_

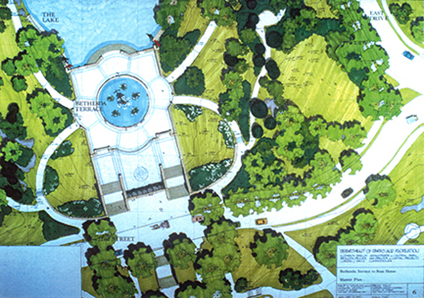

The Master Plan, prepared in 1980 by Philip Winslow and Bruce Kelly, shows the more open landscape planted with lawns and shrubs after removal of trees added in the early 20th century.

The Conservancy spearheaded restoration of the Bethesda Fountain Terrace with work on the center of the lower plaza. Reconstruction of the ornate masonry went hand in hand with landscape architect Philip Winslow’s restoration of the degraded surrounding of slopes of eroded soil, much of which, when wet from rain, slid down to the retaining walls of the Lower Terrace and dislodged much of their stone coping. First, therefore, we repaired and cleaned the crumbling stonework, stabilized the brick paving, rebuilt the original monumental flagpoles (“gonfalons”) at the edge of the lake, re-waterproofed embedded structural elements and removed the ceiling tiles for conservation. Then Phil oversaw the removal of non-original trees that blocked out sunlight, and he designed the replanting of the sloped lawns and shrubs to forestall erosion and to welcome the public for passive enjoyment. The terrace reopened in 1986 and the Arcade ceiling was reinstalled in 2007.

In 1984, I moved to the firm Buttrick White & Burtis (BWB), beginning a happy and productive collaboration with senior partner Harry Buttrick on many structures in the park. We began the restoration of Grand Army Plaza (built to the design of Carrere and Hastings in 1916) at the southeast corner of the park and completed reconstruction in 1990. In addition to the archival research on the original design and preparation of the technical drawings and specifications, part of my assignment was to assist the development team at the Conservancy in raising money for the project. I made presentations to many nearby building owners including Sheldon Solow and Donald Trump. In the process I became acquainted with Deborah Krulewitch, project director of the Conservancy’s project to restore Grand Army Plaza at the southeast entrance to Central Park and public garden designer Lynden Miller. Our collegiality back then laid the groundwork for the lifelong friendship that we still enjoy today.

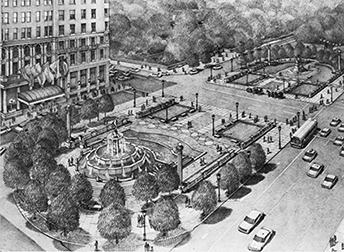

This presentation drawing, prepared for fundraising and agency approvals, shows missing historic elements restored, including the four monumental columns that had been removed in the mid-20th century.

While our Conservancy restoration team rebuilt the fountain plumbing to improve water flow, replaced the soft limestone stone cladding of the fountain exterior with more durable granite, and restored the brick paving of the plaza flooring as well as the, stone benches and adjacent light fixtures, much public attention was focused on the re-gilding of the Saint-Gaudens statue of General Sherman. Although its gold patina was perceived as gaudy by some, the gilding was historically accurate and has been reapplied periodically since then by the Conservancy’s bronze-conservation crew. The architectural features that the Conservancy did not have the funds to restore are the four monumental columns that flanked the northern and southern halves of the plaza until their removal in the 1930’s. Although approval for reconstruction was granted by the Landmarks Preservation Commission and the Art Commission, the columns have still not been replaced, and I sincerely hope that one day replicas of the original ones will again punctuate the plaza’s design.

In the 1980’s our architectural restoration team also completed an extensive renovation of the Loeb boathouse restaurant including enclosing the lakeside terraces for indoor seating and new decorative fencing for the Carousel building, We also prepared a comprehensive survey of all existing masonry or wood structures in Central Park for inclusion in its overall rebuilding plan.

The Ballplayers Refreshment Stand was designed to evoke the richness of the original Vaux architecture with patterned roof shingles, steep gables and a colorful tile frieze of baseballs.

Most challengingly, we designed the first new structures for the park in many years. This was a delicate assignment, given the significance of public attachment to the park’s original design and the need for any new structures to be stylistically compatible if not literal reconstructions. The two new buildings we designed were sited on the location of former ones that had been previously demolished, and the new structures were downsized to suit contemporary needs. The Ballplayers’ Refreshment Stand, designed in collaboration with talented and creative BWB architect Bill Braham, was completed in 1990. Although, its picturesque profile still evokes from a distance the much larger nineteenth-century Boys’ Play House designed by Calvert Vaux, which had been on the site, up close the striped brick walls, the inventive tile frieze featuring baseballs, the patterned slate roof and painted aluminum cresting are clearly modern interpretations of traditional details.

The new Charles A. Dana Center, placed on the site of a derelict 20th century boathouse at the north end of the Harlem Meer, was designed by my partner Samuel G. White with skillful BWB architect Michael M. Dwyer. Hovering at the edge of the Meer, the striking building offers a traditional silhouette with steeply sloped slate roofs and open porches, but inside it has public restrooms and multi-functional educational spaces. We collaborated with Conservancy landscape architect Laura Starr on the surrounding paths and plantings. Construction was completed in 1993.

The more than 15 years I spent researching, restoring or constructing structures in Central Park was truly foundational for my subsequent work on landmark structures and historic landscapes elsewhere. It is an honor to have worked with Betsy Rogers and her talented staff on the rejuvenation of the park in the early days of the Central Park Conservancy.

Share